Originally published on Everyday Feminism Magazine on June 4, 2016 by Jon Greenberg and re-published here with their permission.

We cannot make good decisions

As a teacher deeply invested in transforming a status quo that normalizes human suffering, I have long wanted to help change the systems that create homelessness — long before my three-year-old and I walked around a person sleeping on the pavement at dusk and my child said, “I wouldn’t like to sleep on the ground.”

While homelessness has become increasingly visible where I live, it’s hard to claim that it is a proximate or an immediate part of my daily experiences. However, participating in the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness’s One Night Count brought me — a person who’s never had to experience being homeless — closer, even if only for a couple hours.

Timed with the state’s legislative session, the One Night Count is a volunteer effort to literally count the homeless people of our region so that we can influence government services and policy with hard data, even if the total is a “bare minimum.”

Leading up to the Count, the state seemed severe. Last November, our mayor and county executive jointly declared a state of emergency over homelessness, an action usually reserved for natural disasters – an unprecedented move had Los Angeles, Portland, and Hawaii not previously declared emergencies of their own just weeks earlier.

The Count takes place between 2 and 4 AM. If counting people on the streets, many of whom are sleeping, sounds invasive — you are right. It is.

To respect the autonomy and privacy of the people we’re serving, volunteers and media must follow a strict code of conduct, including staying quiet and keeping a certain amount of distance from people as they sleep.

In my limited experiences, the Count is welcome to those it ultimately serves.

Ten years ago, during the evening of my first Count, in a neighborhood famous for its sidewalks lined with homeless youth, I walked past such a group while discussing with a friend the details of the coming Count. Upon hearing the word “count,” the teenagers leapt up enthusiastically and walked with us for the rest of the block, listing all of the places they sleep that would likely be missed during the Count.

I was not assigned to that neighborhood, however, but rather to Seattle’s waterfront, one of the city’s major tourist attractions. At 3:00 AM, benches, generally littered with tourists during the long summer days, were instead covered with sleeping bodies wrapped in blankets.

A recent visit to that waterfront location taught me who the city prioritizes when tourists and the homeless share space:

Here are seven take-aways, not just from the Count but also from research and an interview with Alison Eisinger, one of the Count’s organizers:

1. Economic ‘Recovery’ Primarily Helps the Wealthy and Middle Class

At the Count’s headquarters, our team of five volunteers was assigned to Seattle’s downtown retail core, sector seven, within walking distance. We headed through Pioneer Square, the nation’s first “Skid Road” and once a neighbor to the shack towns of the Great Depression, the largest and longest economic downturn in modern history. Known as Hoovervilles, these shack towns lasted until the 1940s, when the city finally “systematically eliminated” them.

But you wouldn’t know of this region’s roots of poverty from walking the streets.

New and old buildings, both left and right, were under construction. Due in part to this construction boom, Seattle’s economy is reported to be recovering.

However, while this boom may seem positive – sparkly new buildings, hip new shops – it comes with some catches.

For one, the rich are getting richer while the poor are getting poorer, exacerbating inequality. The top five percent of households may indeed be recovering, but the incomes of the bottom 20 percent are declining. Low-wage jobs are drying up.

Second, construction creates practical problems for the homeless: non-stop noise and activity, as well as the elimination of sidewalks and doorways that once served as refuge.

Finally, the influx of people and money

Whereas Pioneer Square’s nooks and crannies once sheltered many of the city’s homeless, as we departed for sector seven at 2:00 AM, this historic section appeared deserted.

2. Homeless People Are Pushed Out and Stripped of What Little They Have

As our group members noted the vacant streets, our conversation turned to rumors of anti-homeless police sweeps throughout downtown in the weeks leading up to the Count.

Sweeps, euphemistically called “cleanups” by Seattle officials, are removals of unauthorized encampments, during which any personal items encountered by city crews are dumped or temporarily held. Mayor Ed Murray has justified the sweeps by calling unauthorized encampments a “public health” issue.

While such sweeps are common across the country, they are skyrocketing in “progressive” Seattle.

In 2015, the number of sweeps topped 500, compared to just 80 in 2012.

Homeless people, advocates, and now the ACLU have all protested these sweeps, increasingly done by a private company for $240 per hour per cleanup crew. Eisinger calls them not just “ineffective” but also “cruel.” Any outreach that may (or may not) accompany the city crew is essentially “outreach to nowhere.”

All the sweeps really accomplish is chasing the homeless from “encampment to encampment” – and needlessly spending taxpayer dollars that would be far better spent on shelter beds. The number of shelter beds provided by the city and county fall far short of the number of the region’s homeless, the vast majority of whom – 85% – are homegrown.

Tonight’s Count would likely confirm this shortage for yet another year.

3. Homeless People Are Too Often Denied Their Most Basic Human Rights

As we approached our sector, we started spotting the human bodies, most often sleeping in doorways.

Seeing the bodies, especially the ones on their feet, brought back the words of Wes Browning, a formerly homeless man and writer for Real Change, who has spoken to my classes many times over the years: “The hardest part about being homeless is the lack of sleep.”

Sleep.

I know I’m worthless without it. Sleep is the reason why I almost declined Eisinger’s invitation. Without one night of good sleep, my teaching crumbles and my health buckles.

One clear consequence of sleep deprivation is that homeless people die much younger, often from chronic diseases that are “exacerbated by a lack of rest,” according to Eisinger.

When we think of the challenges of the homeless, we often think shelter, exposure to the elements. Homeless, right? As we tallied another person, my thoughts remained fixed on the importance of sleep, a luxury not shared by the humans we counted.

4. Our Community Prioritizes Denial and Ignorance Over the Humanity of the Homeless

Though we steadily accumulated tally marks, the number was lower than we expected considering our location in the heart of downtown, where, during the day, homeless people are almost as common as shoppers and business suits.

The vacant streets could have been attributed to the sweeps, but it seemed that there were many more forces in play pushing homeless people out.

Alleys had been recently hosed down and cleaned, the suds still drying, the chemicals still lingering in the 50° air.

Many alleys were so brightly lit, it might as well have been 2:30 PM, not AM. And if the frequent signage warning that “trespassers will be prosecuted” didn’t chase a human off, the building security guard who followed us into one alley most certainly would have.

Instead of solving homelessness, the business community and City of Seattle collude to send a very clear message: homeless people are not welcome here.

This collusion has led to the erosion of public amenities, such as public restrooms. Taking a shit has somehow become a privilege.

This collusion also depends on what Eisinger describes as a “false premise”: if the homeless go away, we have solved homelessness.

It’s a premise that contributes to what Eisinger calls the “suburbanization of poverty.” As the homeless are pushed out of the city, they are forced into surrounding municipalities, which, compared to Seattle, spend a fraction of their budgets on services for the homeless.

In these same areas, Eisinger says that the numbers of “unsheltered homelessness has increased by 53%.”

Both the message and the premise are firmly grounded in denial.

The one business not sending an unwelcome message was, oddly, Macy’s. According to one of our team members, Macy’s employees are instructed to leave be the homeless people who line the sidewalks at night. As we looped around Macy’s to work our way back toward headquarters, we counted dozens of homeless people, an island of humanity in a sea of inhospitality.

On the sidewalks of Macy’s, we encountered most of the few homeless women we counted.

5. Homeless Women Are Particularly Vulnerable

Despite our low count of women, America has the “largest number of homeless women and children in the industrialized world,” according to The Atlantic.

Given the high rates of violence against women – especially transgender women of Color – women are particularly vulnerable on the streets. One nonprofit reports that over 92% of homeless mothers have experienced “severe physical and/or sexual abuse.”

Perhaps that’s why nearly every woman we counted was paired with a man: for protection.

The hashtag #TheHomelessPeriod reveals that violence is not the only less-acknowledged challenge that homeless people experience. Expensive and often unavailable at shelters, tampons and pads are among the top needs of homeless people who menstruate.

I confess that the intersection of menstruation and homelessness was the furthest thing from my mind as we entered the 3 o’clock hour. Instead, my thoughts turned to my school’s youth facing homelessness.

6. Homelessness Is as Intersectional as Our Feminism Needs to Be

In Seattle Public Schools alone, there are 3,000 homeless students. In the state, there are 35,000. In the nation, there are 1.36 million. Children.

Homeless youth are “prey” for sex-traffickers and 50% of the city’s homeless youth are “LGBT youth.”

If we are to understand homelessness, then we need to better understand the vast web of social injustices – as homelessness is connected to virtually every one of them. A few examples:

It’s connected to racism. In Seattle, Black Americans make up just 7% of the city’s population but account for 41% of people in emergency shelters.

It’s connected to our health care system. USA Today estimates that one-fifth of this country’s homeless have a “severe mental illness.” Truthout puts the number closer to a third of the homeless with “untreated mental illnesses.” Instead of receiving treatment, mentally ill people are too often funneled into prisons.

It’s connected to our criminal “justice” system. Despite Mayor Ed Murray’s claim that homelessness is a “public health” issue, our governments too often criminalize homelessness – outlawing resting on benches, sleeping in cars – forcing the police to lock up the homeless (at least those they don’t kill). Hell, we even criminalize feeding the homeless.

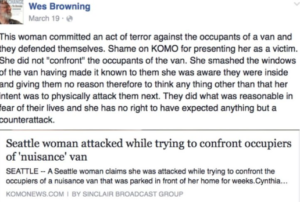

In fact, homeless people are more likely to be a victim of a crime than a perpetrator, as Wes Browning shows us in this misreported case:

likely to be a victim of a crime than a perpetrator, as Wes Browning shows us in this misreported case:

7. Homelessness Is Increasing

We returned to the headquarters close to 3:30 AM. Our tally sheet recorded 70 homeless people counted by our group of five in about 90 minutes.

As we sat down to eat a breakfast served to the volunteers, over 1,000 of them, I wondered if what seemed like a “community” effort to drive out the homeless had succeeded in lowering the number.

It wasn’t until between classes that day that I read the headline: “New One-Night Count Numbers Show 19 Percent Increase in Unsheltered Homelessness Across King County”

4,505 people. This year’s total was again a double-digit percent increase over the previous year’s total.

And that total represents just a snapshot, a bare minimum, a “rough sketch,” of unsheltered humans in one city. And the numbers continue to rise in urban centers across the country.

***

How the hell did we get to this point?

Our collective denial has obscured the humanity of too many among us for too long. People deserve dignity, not denial.

By recognizing the humanity of the homeless, we might very well regain some of our own.

On a personal level, we must, as Eisinger asserts, “broaden what a civil society looks like.”

A civil society means sharing space – buses, libraries, cafes, neighborhoods – with homeless people. It means supporting businesses that treat homeless people with respect. It means buying homeless people gifts cards to such businesses so that they can actually meet their most basic of needs: rest, nourishment, bathroom access.

On a societal level, we must demand nothing short of a dramatic and drastic reprioritization of resources.

In part because of racist housing practices, the market has allowed some to cash in on home ownership while millions today struggle to find decreasingly available affordable housing.

To make matters worse, over the course of four decades, the federal government has abandoned its support of affordable housing. Even if you qualify for federally subsidized housing, good luck finding a landlord to rent to you in Seattle.

An incremental approach to solving homelessness will not fix these failures.

As Eisinger says, with an incremental approach, we are essentially saying to the homeless, we’ll help only a few of you and while the rest of you wait, we don’t want you.

Providing affordable housing is not only the moral course of action but it’s also more effective and cheaper than our current mess of a system. The Housing First method – through which homeless people receive housing before help with other issues like mental health, addiction, and employment – has proved effective, particularly with those who are chronically homeless.

Salt Lake City made headlines after implementing Housing First reduced its chronic homelessness by 91 percent. Let’s build on that.

“We need to make affordable housing one of the top three priorities for every elected official at every level of government in this country,” says Eisinger.

Bryan Stevenson states that the opposite of poverty is not wealth. It’s justice.

Let’s work for justice.

Jon Greenberg is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. He is an award-winning public high school teacher in Seattle who has gained broader recognition for standing up for racial dialogue in the classroom — with widespread support from community — while a school district attempted to stifle it. To learn more about Jon Greenberg and the Race Curriculum Controversy, visit his website citizenshipandsocialjustice.com. You can also follow him on Facebook, Tumblr, and Twitter @citizenshipsj.