Originally published on the Huffington Post on December 11, 2015 By Amy Oestreicher.

Many survivors “know” that being sexually assaulted was not their fault. Now, I’m one of them. But the question I’ve worked to answer after a decade of “healing” and “processing” what happened to me is, “Well, then why didn’t I do something?”

I had heard this dozens and dozens of times — in my own head and with students who have opened up to me during my programs. Many victims of abuse, molestation and domestic violence often feel a guilt that they are not deserving of. For months after my voice teacher molested me, I beat myself up thinking, “Why did I do that?” wondering, “What was I thinking?” and assuming “Something must be wrong with me.”

It also took me a very long time to accept that a mentor and father figure in my life had violated our trusting relationship. I kept replaying the events that had occurred in my mind, telling myself, I must have done something wrong — why else would he have done this? I must have instigated something… I blamed myself, convinced that no one could take advantage of me if I had not invited it.

I couldn’t shake off this “shame” I felt no matter how hard I tried to forget what had happened. The more I tried to block my memories, the more anxious and confused I became. I became a space cadet — hardly feeling at all. It was how I protected myself. This way, I couldn’t feel the sense of loss and betrayal. I couldn’t feel the shame of still thinking this was all “my fault.” My numbness started to alarm my friends and family, to whom I insisted that nothing was wrong at all. I kept this secret hidden inside, burning in my gut, hidden from those I loved.

The more I tried to repress what had happened, the more anxious I became, until I couldn’t handle keeping these secrets locked up so tightly. shocked, upset and as overwhelmed I was living in three worlds — part of me functioning normally in school, keeping up my grades, and telling people I was “fine”, part of me replaying traumatic memories in my head, beating myself up for not saying no, for not running away, for not fighting back, and part of me in a numb, apathetic space of disconnect — a place I created in my head as a survival instinct. If I created a frozen, “numb” space to exist in, I could alleviate the sense of shame I felt.

When I turned 18, I finally spilled everything to my mother. I was so afraid of what she might say or if she would judge my actions. I was embarrassed to say words like “sex” and “molestor” and “rape” out loud, let alone with my mother. My mother was as shocked I was. But she still provided me with the one solid anchor that I needed. She told me it was not my fault. No matter what I told her I had done, what he had done, what details I could remember, or what I confided in her, she reassured me with the certainty only a mother can have: it was not your fault.

Reaching out to someone I knew loved me unconditionally calmed my anxiety. Telling someone what had happened made my “dark” secret come to light. I became open to viewing my abuse in a different way — I was willing to take some of the responsibility off of myself. My mother and I started reading about “trauma.”

I learned that in the face of trauma, you can have three responses: You can fight, flee or freeze. I could have immediately fought back against my abuser, yelling “no” or defying him in some way. I could have just ran in the other direction as fast as I could. But I was so shocked by everything that happened that I froze. Like a deer in the headlights, I couldn’t come to terms with the idea that a man that I trusted as my mentor could turn into such a monster in the blink of an eye. I mentally left the situation, disassociated from my body, and became a passive bystander to a trauma that my body was directly involved in.

I learned that the physical sensations of “guilt” register in the same way that “shame” and “helplessness” do in your body — so when a person feels helpless in a situation, the body automatically pairs that sensation with “guilt.” When you undergo any kind of trauma it causes a disturbance in your energy flow — suddenly, you are unable to feel those emotions that once came so naturally at a time. My body stopped breathing the same way it used to — a big knot of tension evolved in my chest and remained there like a cocoon. My thoughts became rigid — frightened to wander into past memories. I put up a daze like four safe walls that protected me from being consciously present in the abuse, and that daze stayed with me with or without him. I lived in a world separate from everyone else.

Reaching out not only gave me the blessing of compassion from others — it also informed me of what I had really experienced. I realized my “numb” response to my assault, my nervous energy, sweating fits and anxiety attacks were not something to be ashamed of, but rather, a proud and victorious survival strategy.

In a wonderful book, Waking the Tiger, Peter Levine writes, “All mammals automatically regulate survival responses from the primitive, non-verbal brain, mediated by the autonomic nervous system. Under threat, massive amounts of energy are mobilized in readiness for self-defense via the fight, flight, and freeze responses. Once safe, animals spontaneously ‘discharge’ this excess energy through involuntary movements including shaking, trembling, and deep spontaneous breaths. This discharge process resets the autonomic nervous system, restoring equilibrium.”

Suddenly, I felt understood. Now, when I work with survivors, I help them realize that their reactions to trauma and assault are natural human reactions to be applauded. The real work comes from taking that nervous energy, which was formerly an essential trauma survival skill, and turning it into productive healing energy — energy that once redirected, can build a new, beautiful world for the survivor.

The biggest gift I can give to survivors I work with in my program now, is the gift of a world in color — alive with melancholy blues, angry reds, uncertain grays, but also one of ecstatic oranges, bright yellows, and deep rich purples. Once we let ourselves feel the “bad”, we make room for the “good”.

I was sexually abused. It was not my fault. In a traumatizing situation, I froze, while others might have fled or fought back. But with time and with confiding in those I trust, I have unthawed and faced what I’ve tried to forget. And with nothing to hide, nothing to regret or redo, and everything to look forward to in the future, I’ve allowed myself to move on, claiming my voice, speaking my truth.

As survivors, the most wonderful part of healing is moving from a helpless situation into a world of our own design. Now that we’ve relied on the instinctual survival skill of freezing,” we’ve kept our spirits in tact, and now, we’re unstoppable.

So what is shame? Shame is energy. As we turn that energy into energy that is rightfully ours, the energy of survival, pride and life, we become forces to be reckoned with.

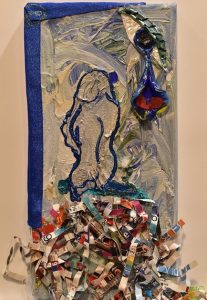

Amy works directly with survivors of sexual assault and those healing from PTSD. Learn more about her college sexual assault prevention initiative here. All artwork was created by Amy as a way to heal from her own history of sexual assault.

Follow Amy Oestreicher on Twitter: www.twitter.com/amyoes

Amy Oestreicher

PTSD peer-peer specialist, artist, author, survivor, award-winning founder of the Fearless Ostomates, actress and playwright touring the country with Gutless & Grateful, her one-woman musical autobiography. More information at amyoes.com.