Originally published in the Detroit Free Press on February 1, 2015 By Bill Laitner. Photos By Ryan Garza

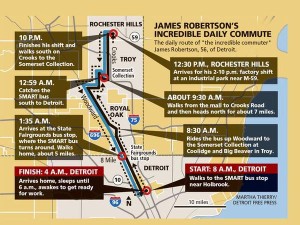

He doesn’t look athletic but James Robertson, 56, of Detroit has a champ’s commute. He rides buses part-way but walks about 21 miles in round trips to a factory, unless his banker pal offers a lift.

Leaving home in Detroit at 8 a.m., James Robertson doesn’t look like an endurance athlete.

Pudgy of form, shod in heavy work boots, Robertson trudges almost haltingly as he starts another workday.

But as he steps out into the cold, Robertson, 56, is steeled for an Olympic-sized commute. Getting to and from his factory job 23 miles away in Rochester Hills, he’ll take a bus partway there and partway home. And he’ll also walk an astounding 21 miles.

Five days a week. Monday through Friday.

It’s the life Robertson has led for the last decade, ever since his 1988 Honda Accord quit on him.

Every trip is an ordeal of mental and physical toughness for this soft-spoken man with a perfect attendance record at work. And every day is a tribute to how much he cares about his job, his boss and his coworkers. Robertson’s daunting walks and bus rides, in all kinds of weather, also reflect the challenges some metro Detroiters face in getting to work in a region of limited bus service, and where car ownership is priced beyond the reach of many.

But you won’t hear Robertson complain — nor his boss.

“I set our attendance standard by this man,” says Todd Wilson, plant manager at Schain Mold & Engineering. “I say, if this man can get here, walking all those miles through snow and rain, well I’ll tell you, I have people in Pontiac 10 minutes away and they say they can’t get here — bull!”

As he speaks of his loyal employee, Wilson leans over his desk for emphasis, in a sparse office with a view of the factory floor. Before starting his shift, Robertson stops by the office every day to talk sports, usually baseball. And during dinnertime each day, Wilson treats him to fine Southern cooking, compliments of the plant manager’s wife.

“Oh, yes, she takes care of James. And he’s a personal favorite of the owners because of his attendance record. He’s never missed. I’ve seen him come in here wringing wet,” says Wilson, 53, of Metamora Township.

With a full-time job and marathon commutes, Robertson is clearly sleep deprived, but powers himself by downing 2-liter bottles of Mountain Dew and cans of Coke.

“I sleep a lot on the weekend, yes I do,” he says, sounding a little amazed at his schedule. He also catches zzz’s on his bus rides. Whatever it takes to get to his job, Robertson does it.

“I can’t imagine not working,” he says.

‘Lord, keep me safe’

The sheer time and effort of getting to work has ruled Robertson’s life for more than a decade, ever since his car broke down. He didn’t replace it because, he says, “I haven’t had a chance to save for it.” His job pays $10.55 an hour, well above Michigan’s minimum wage of $8.15 an hour but not enough for him to buy, maintain and insure a car in Detroit.

As hard as Robertson’s morning commute is, the trip home is even harder.

At the end of his 2-10 p.m. shift as an injection molder at Schain Mold’s squeaky-clean factory just south of M-59, and when his coworkers are climbing into their cars, Robertson sets off, on foot — in the dark — for the 23-mile trip to his home off Woodward near Holbrook. None of his coworkers lives anywhere near him, so catching a ride almost never happens.

Instead, he reverses the 7-mile walk he took earlier that day, a stretch between the factory and a bus stop behind Troy’s Somerset Collection shopping mall.

“I keep a rhythm in my head,” he says of his seemingly mechanical-like pace to the mall.

At Somerset, he catches the last SMART bus of the day, just before 1 a.m. He rides it into Detroit as far it goes, getting off at the State Fairgrounds on Woodward, just south of 8 Mile. By that time, the last inbound Woodward bus has left. So Robertson foots it the rest of the way — about 5 miles — in the cold or rain or the mild summer nights, to the home he shares with his girlfriend.

“I have to go through Highland Park, and you never know what you’re going to run into,” Robertson says. “It’s pretty dangerous. Really, it is (dangerous) from 8 Mile on down. They’re not the type of people you want to run into.

“But I’ve never had any trouble,” he says. Actually, he did get mugged several years ago — “some punks tuned him up pretty good,” says Wilson, the plant manager. Robertson chooses not to talk about that.

So, what gets him past dangerous streets, and through the cold and gloom of night and winter winds?

“One word — faith,” Robertson says. “I’m not saying I’m a member of some church. But just before I get home, every night, I say, ‘Lord, keep me safe.’ “

The next day, Robertson adds, “I should’ve told you there’s another thing: determination.”

A land of no buses

Robertson’s 23-mile commute from home takes four hours. It’s so time-consuming because he must traverse the no-bus land of rolling Rochester Hills. It’s one of scores of tri-county communities (nearly 40 in Oakland County alone) where voters opted not to pay the SMART transit millage. So it has no fixed-route bus service.

Once he gets to Troy and Detroit, Robertson is back in bus country. But even there, the bus schedules are thin in a region that is relentlessly auto-centric.

“The last five years been really tough because the buses cut back,” Robertson says. Both SMART and DDOT have curtailed service over the last half decade, “and with SMART, it really affected service into Detroit,” said Megan Owens, executive director of Transportation Riders United.

Detroit’s director of transportation said there is a service Robertson may be able to use that’s designed to help low-income workers. Job Access and Reverse Commute, paid for in part with federal dollars, provides door-to-door transportation to low-income workers, but at a cost. Robertson said he was not aware of the program.

Still, metro Detroit’s lack of accessible mass transit hasn’t stopped Robertson from hoofing it along sidewalks — often snow-covered — to get to a job.

At home at work

Robertson is proud of all the miles he covers each day. But it’s taking a toll, and he’s not getting any younger.

“He comes in here looking real tired — his legs, his knees,” says coworker Janet Vallardo, 59, of Auburn Hills.

But there’s a lot more than a paycheck luring him to make his weekday treks. Robertson looks forward to being around his coworkers, saying, “We’re like a family.” He also looks forward to the homemade dinners the plant manager’s wife whips up for him each day.

“I look at her food, I always say, ‘Excellent. No, not excellent. Phenomenal,’ “ he says, with Wilson sitting across from him, nodding and smiling with affirmation.

Although Robertson eats in a factory lunchroom, his menus sound like something from a Southern café: Turnip greens with smoked pork neck bones, black-eyed peas and carrots in a brown sugar glaze, baby-back ribs, cornbread made from scratch, pinto beans, fried taters, cheesy biscuits. They’re the kind of meal that can fuel his daunting commutes back home.

Though his job is clearly part of his social life, when it’s time to work this graduate of Northern High School is methodical. He runs an injection-molding machine the size of a small garage, carefully slicing and drilling away waste after removing each finished part, and noting his production in detail on a clipboard.

Strangers crossing paths

Robertson has walked the walk so often that drivers wonder: Who is that guy? UBS banker Blake Pollock, 47, of Rochester, wondered. About a year ago, he found out.

Pollock tools up and down Crooks each day in his shiny black 2014 Chrysler 300.

“I saw him so many times, climbing through snow banks. I saw him at all different places on Crooks,” Pollock recalls.

Last year, Pollock had just parked at his office space in Troy as Robertson passed. The banker in a suit couldn’t keep from asking the factory guy in sweats, what the heck are you doing, walking out here every day? They talked a bit. Robertson walked off and Pollock ruminated.

From then on, Pollock began watching for the factory guy. At first, he’d pick him up occasionally, when he could swing the time. But the generosity became more frequent as winter swept in. Lately, it’s several times a week, especially when metro Detroit sees single-digit temperatures and windchills.

“Knowing what I know, I can’t drive past him now. I’m in my car with the heat blasting and even then my feet are cold,” Pollock says.

Other times, it’s 10:30 or 11 p.m., even after midnight, when Pollock, who is divorced, is sitting at home alone or rolling home from a night out, and wondering how the man he knows only as “James” is doing in the frigid darkness.

On those nights, Pollock runs Robertson all the way to his house in Detroit.

“I asked him, why don’t you move closer” to work. “He said his girlfriend inherited their house so it’s easy to stay there,” Pollock said.

On a recent night run, Pollock got his passenger home at 11 p.m. They sat together in the car for a minute, outside Robertson’s house.

“So, normally you’d be getting here at 4 o’clock (in the morning), right?” the banker asks. “Yeah,” Robertson replies. Pollock flashes a wry smile. “So, you’re pretty early, aren’t you?” he says. Robertson catches the drift.

“Oh, I’m grateful for the time, believe me,” Robertson says, then adds in a voice rising with anticipation: “I’m going to take me a bath!”

After the door shuts and Pollock pulls away, he admits that Robertson mystifies him, yet leaves him stunned with admiration for the man’s uncanny work ethic and determination.

“I always say to my friends, I’m not a nice guy. But I find myself helping James,” Pollock says with a sheepish laugh. He said he’s picked up Robertson several dozen times this winter alone.

Has a routine

At the plant, coworkers feel odd seeing one of their team numbers always walking, says Charlie Hollis, 63, of Pontiac. “I keep telling him to get him a nice little car,” says Hollis, also a machine operator.

Echoes the plant manager Wilson, “We are very much trying to get James a vehicle.” But Robertson has a routine now, and he seems to like it, his coworkers say.

“If I can get away, I’ll pick him up. But James won’t get in just anybody’s car. He likes his independence,” Wilson says.

Robertson has simple words for why he is what he is, and does what he does. He speaks with pride of his parents, including his father’s military service.

“I just get it from my family. It’s a lot of walking, I know.”

Contact Bill Laitner: blaitner@freepress.com or 313-223-4485.