Originally published in the Boston Globe on August 20, 2002 By Michael Rezendes.

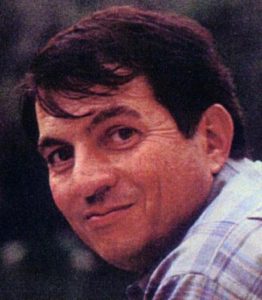

Brian O’Connor, who says he was molested by two priests from Our Mother of Sorrows Church in Tucson, said a bishop was the first to sexually abuse him.

TUCSON – When Monsignor Robert C. Trupia was confronted by his superiors in 1992 with an accusation that he had sexually molested an altar boy, he replied with a pointed warning: Pursue the charge and he would go public with information about an Arizona bishop’s sex life, with scandalous results for the Roman Catholic Diocese of Tucson.

Church officials thought they knew what he was threatening to reveal, that he’d had a sexual relationship

with James S. Rausch, the late bishop of Phoenix, according to sealed court documents, including church records, obtained by the Globe.

But Trupia’s secret was much more explosive. The documents obtained by the Globe, including a secret affidavit in a clergy sexual abuse lawsuit, allege that Rausch, Trupia, and the late Rev. William T. Byrne all had sex during the late 1970s and early 1980s with a Tucson teenager who was later given a chancery job to ensure his silence.

Trupia’s explicit threat is part of the sealed evidence in 11 civil lawsuits against Trupia, Byrne, and two other priests that were settled earlier this year by the Tucson Diocese for a sum estimated at $14 million by people familiar with the details. Church officials said they plan to defrock Trupia, who was described recently by Tucson diocese spokesman Fred Allison as “an artful, manipulative, intelligent, and highly skilled pedophile.”

But in a troublesome signal for American bishops who have committed themselves to tougher sanctions against abusers, the ouster of Trupia has been blocked by the Vatican’s highest tribunal, which sided with Trupia after he appealed an earlier effort to suspend him. Trupia, 54, who is living in Maryland, receives a salary of $1,200 a month and health insurance. He has been removed from active ministry.

“The diocese blames Rome, Rome blames the diocese, and nothing gets done,” said Lynne M. Cadigan, an attorney who represented Trupia’s alleged victims in the settled lawsuits.

Evidence in the lawsuits (most of which is sealed under a court order) was reviewed by the Globe and includes an affidavit by the former teenager, Brian F. O’Connor, that was given to Cadigan two months before the settlement. Now 40, O’Connor recently provided church officials with further details of his allegations, saying that he was molested as a teenager on numerous occasions by Rausch, then passed along to Byrne and Trupia, ostensibly for drug counseling.

“I wasn’t one of those angelic kids who got picked up on the altar and abused in the sacristy, but I didn’t deserve what happened to me,” O’Connor said in an interview. He said he was still a minor when Rausch molested him but had reached 18, the age of consent, by the time Trupia had sex with him.

Diocesan spokesman Allison declined to comment about the allegations that the bishop and two priests had molested the same teenager. The recent settlement, however, covered allegations by others against both Byrne and Trupia.

Trupia’s alleged attempt at blackmail is not the first one to surface since the clergy sexual abuse scandal erupted in January. Records from the Boston archdiocese, for example, show that the Rev. Paul R. Shanley, who has been indicted on child rape charges, tried to prevent the late Cardinal Humberto S. Medeiros from ending Shanley’s controversial street ministry by threatening to go public with revelations about St. John’s Seminary. Years later, Shanley also wrote to a church official saying he had kept his own alleged sexual abuse by an unnamed former cardinal to himself.

Like Shanley’s warnings, Trupia’s 1992 attempt to intimidate Tucson Bishop Manuel D. Moreno into revoking a suspension and an order that he undergo a psychiatric evaluation is also documented by church records, including the 1995 letter written by Trupia to Moreno.

In the letter, Trupia recounts the 1992 meeting with Moreno and Moreno’s chancellor and notes: “I informed you of my direct knowledge regarding another bishop’s activities, which knowledge was potentially of a highly explosive and damaging nature to the Church in Arizona.”

“Let me assure you again,” Trupia continues in the letter, “that I would not want to be put into a position to be subpoenaed and have to testify under oath as to what I know about this other bishop. At the same time, I am growing quite weary of trying to stand between the Church in Arizona and a torrent of bad publicity that your attempted actions continue to make ever more likely.”

Trupia’s attorney, Stephen Shechtel, said he would not characterize the letter as blackmail. “It’s Father Trupia saying, `Hey, Father Moreno, don’t make me out to be the fall guy because I’m not the one who has done a lot of this stuff.’ “

Memories dredged up

Until recently, O’Connor was content to try to forget his youth as a heroin addict and a six-year employee of the Tucson chancery. He and his gay partner were raising an adopted son and he was busy running an auto repair business.

But late last year he was contacted by a county investigator and later by attorney Cadigan, who was representing 11 men and five of their parents in the sexual abuse lawsuits against Trupia, Byrne, and two other priests that have been settled.

On Nov. 28, 2001, O’Connor signed an affidavit for Cadigan saying that in the summer of 1979, when he was 17, Rausch picked him up on a Tucson street, had sex with him, then sent him to Trupia for counseling. O’Connor also said Trupia had sex with him before hiring him as a temporary assistant at the chancery, where Trupia was a vice chancellor in charge of the marriage tribunal.

Still, in the Globe interview, O’Connor expressed ambivalent feelings about Trupia. Trupia helped him shake his drug habit and purchase a home, he said. But as news coverage of the Tucson settlement and the national scandal exploded, O’Connor said, he grew increasingly troubled by memories of the abuse and drafted a written statement he delivered to Tucson Bishop Gerald F. Kicanas, who has been named as Moreno’s prospective successor, and the Rev. Van A. Wagner, the diocese’s vicar general.

O’Connor said he has not filed a lawsuit but has asked for a financial settlement of his claims.

In his written account to the diocese in April, a copy of which was reviewed by the Globe, and in several interviews, O’Connor said that when he met Rausch in 1979, the bishop, who identified himself only as “Paul,” drove up beside him and offered him a ride. After getting into the car, O’Connor said, he initially resisted Rausch’s offer of $50 to allow Rausch to perform oral sex on him, but eventually agreed.

Throughout the summer and fall, a period when O’Connor became addicted to heroin, Rausch contacted him for additional exchanges of sex for money, O’Connor said. Once, he said, Rausch left him alone in his car while registering for a motel room. O’Connor, rifling Rauch’s glove compartment, discovered that “Paul” was really Bishop Rausch, and confronted him.

“He explained that he was only relieving stress and any number of other excuses for acting out his libido,” O’Connor wrote in his statement.

By that time, Rausch was also concerned about O’Connor’s drug use and, after a few additional encounters, said he wouldn’t call again. But he recommended that O’Connor contact either Byrne or Trupia, a priest at the parish, for drug counseling, and said O’Connor should use Rausch’s name if he reached either of them.

In a recent interview, O’Connor said that months later, in 1980, he located Trupia at Our Mother of Sorrows Church in Tucson but was referred to Byrne, the pastor, who began counseling him on a regular basis, typically at private homes in the area. More often than not, O’Connor said, he would show up high and Byrne would end the sessions by offering him a drink and then sexually molesting him.

Over the next year, O’Connor said, he stayed away from the church and grew more addicted to heroin, although he continued working temporary jobs and also sold drugs. Then, in 1981, he and some friends accepted a ride from someone O’Connor did not immediately recognize. But after climbing into the front seat, he said, he saw that it was Trupia behind the wheel.

Halting an addiction

After Trupia dropped O’Connor’s friends off, O’Connor said, the young man erupted in anger over the memory of Byrne’s abuse, pummeling Trupia and, when Trupia stopped, leaping from the car and slamming his fist into the side of a dumpster. “The next thing I knew he was standing over me, caressing my head and I was just sobbing,” O’Connor said. “He told me, ‘I’m only here because you came for help and I know you didn’t get it. I only want to help you.’ “

O’Connor said that he rejected Trupia’s help but that Trupia kept returning to the neighborhood and eventually persuaded him to share a meal. Soon, O’Connor said, he was meeting Trupia daily, mapping out a plan to gradually reduce the amount of heroin he was using. When Trupia decided O’Connor was ready to stop using completely, O’Connor said, Trupia took him to St. John’s College Seminary in Camarillo, Calif., in the Los Angeles Archdiocese, and stayed with him in a room until the sickness that comes with heroin withdrawal subsided.

When O’Connor was free of the drug, he said, Trupia persuaded him to begin a sexual relationship. “I felt I owed a great debt to him and he claimed to have fallen in love with me,” O’Connor said in his statement. But the sex didn’t last, he said. “I was getting better and I started feeling like it was a sick relationship,” O’Connor explained. Still, according to O’Connor, he and Trupia remained friends, and in 1982, Trupia hired O’Connor as a temporary employee at the chancery’s matrimonial tribunal. Byrne also worked there.

O’Connor said he grew increasingly troubled by his experiences with Rausch, Byrne, and Trupia. Yet his attempt to speak with Moreno was rebuffed, he said. So, he said, he arranged to meet with Moreno’s predecessor, retired Bishop Francis J. Green, and told Greenthe story.

“He asked me if I would be willing to agree to keep the story quiet so as not to cause harm to the church,” O’Connor said in his statement. O’Connor said Green, who died in 1995, also arranged for O’Connor – a high school dropout and a non-Catholic – to receive a full-time appointment at the marriage tribunal as “apparitor,” or arm of the bishop.

At one point, O’Connor said, church officials concerned about an investigation into Trupia’s activities sent O’Connor away, out of investigators’ reach, on a three-month paid vacation to a rural area in the Eastern United States. O’Connor said he doesn’t know who was conducting the inquiry, but court records show that O’Connor’s vacation coincided roughly with a Tucson police investigation and longstanding complaints from officials at St. John’s College Seminary in California that Trupia often visited with unauthorized young, male guests.

“I continued working for the diocese through 1988 when I left the diocese totally disillusioned,” O’Connor said in his written statement.

Rome steps in

Although details of the legal and financial settlement between the church and Trupia’s alleged victims are secret, Allison, the Tucson Diocese spokesman, did not hesitate to brand Trupia as a pedophile.

Indeed, the sealed church records show that Trupia was repeatedly accused of molesting children during his 18 years as an active priest, first in Yuma and later in Tucson, and that his abuse became so widely known that other priests referred to him as a “chicken hawk.”

“He remains in total denial of his multiple and serial acts of abuse and basically cannot or will not accept any responsibility for them,” Allison said.

The standoff between Trupia and the diocese began with Trupia’s meeting with Moreno on April 1, 1992, after Trupia had returned from three years of study for a canon law degree at Catholic University in Washington.

According to affidavits Moreno sent to Rome, when Moreno and his chancellor, the Rev. John Alt, confronted Trupia with the allegation that he’d molested an altar boy, Trupia described himself as a “loose cannon” unfit for the priesthood. He also asked to be retired as a priest in good standing. But Moreno rejected the idea, insisting on a suspension and an order requiring him to undergo a physical and psychiatric evaluation.

Trupia, after making his threat, appealed his suspension to the Vatican and in 1997 won a favorable ruling. The ruling, a copy of which was among the sealed court documents obtained by the Globe, ordered Moreno to reevaluate Trupia’s proposal to be retired in good standing, and said the diocese must reimburse Trupia for legal expenses. The ruling made no mention of the sexual abuse allegations.

On Dec. 22, 1997, Moreno protested that decision in hopes the Vatican would take a tougher stance. So far, there has been no decision.

Noting that one of Trupia’s alleged victims had “threatened to go to the newspapers” and that a sexual abuse lawsuit had been filed, Moreno wrote, “I cannot take these risks with the lives of others and the patrimony of this diocese without an evaluation of Msgr. Trupia which would indicate that he is no longer a threat to the people of God.”

In April 2002, after American cardinals met with the pope to discuss the scandal, the cardinals said they would propose canon law revisions that would make it easier for diocesan bishops to dismiss priests who had abused minors. The Vatican has yet to signal whether that proposal or other reforms approved by the cardinals will be adopted.

In the meantime, Allison said last week that he has no reason to believe Trupia has had the medical and psychiatric evaluation ordered by Moreno more than a decade ago. Also, he said, the dispute over Trupia’s suspension remains unresolved. “It’s just been sitting at the Vatican,” he said.