Originally published in the Boston Globe on March 14, 2002 By Michael Rezendes.

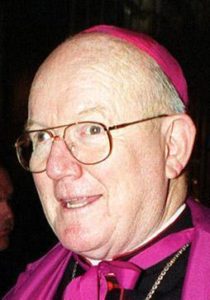

NEW YORK – Although he has led the Brooklyn Diocese for more than a decade, the Most Rev. Thomas

V. Daily has been shadowed by his Boston past. In 56 lawsuits settled Monday, Daily, along with other church supervisors, was accused of covering up multiple child molestations by former priest John J. Geoghan when Daily was a bishop in the Boston Archdiocese 20 years ago.

Daily is also accused of brushing aside sexual abuse allegations made here only four years ago, when a New Jersey priest and his brother told church officials they were molested as children by a Brooklyn priest now serving as one of Daily’s pastors.

Thomas V. Daily is a former aide to Cardinal Law.

The Rev. Timothy J. Lambert, a 44-year-old clergyman on a leave of absence, made the allegations in a 1998 meeting with diocesan leaders. And his attorney repeated them a year later in an eight-page letter to Daily that described Lambert’s charges of abuse by a priest who had become a fixture at his home, where Lambert’s mother was struggling to raise four sons and a daughter on her own.

“That set up the perfect situation for a predator,” said the letter, which identified the accused priest as the Rev. Joseph P. Byrns, now pastor at Brooklyn’s St. Rose of Lima Church.

Written by New Jersey lawyer Stephen C. Rubino, the letter provided details of years of alleged abuse by Byrns, while painting a portrait of Lambert as a troubled youngster eager for affection from someone who could fill the gap left by his absent, alcoholic father.

“Fr. Byrns knew that many of his sexual needs would be satisfied by this young boy as long as he successfully groomed him with pseudo-affection and gifts, which represented to this child the love no other male figure, particularly his father, had ever given him,” the letter to Daily said.

In a brief telephone interview, Byrns said he has known the Lambert family since 1969 but denied the accusations of abuse made by Lambert and his brother. “There’s nothing to the story,” Byrns said.

Daily, through a spokesman, said he believes Byrns but declined to comment directly.

A Belmont native and former bishop of the Palm Beach, Fla., Diocese, Daily has led the Brooklyn Diocese – which includes the borough of Queens and is the fifth largest in the nation, behind the Boston Archdiocese – since 1990.

Earlier, as a deputy to the late Cardinal Humberto Medeiros and to Cardinal Bernard F. Law, Daily played a central role in moving Geoghan from parish to parish after he and others had discovered Geoghan was a serial child molester.

Court documents show Daily knew Geoghan was an abuser as early as 1980, when a Jamaica Plain priest told him Geoghan had admitted to molesting seven boys from the same extended family.

The documents also show Daily met with members of that family, one of whom said Daily asked them to keep the abuse secret, while Geoghan was sent on sabbatical to Rome and later transferred to a Dorchester church, where he allegedly abused more children.

More recently, a spokesman for Daily said in response to questions from the Globe that Daily has reviewed the allegations made by Lambert and his older brother, Robert, but has concluded Byrns is innocent and considers the case closed.

The spokesman, Frank De Rosa, said a diocesan investigation went no further than interviews with

Bryns and other church officials. “Fr. Byrns has repeatedly denied in a very strong and meaningful way that anything took place,” DeRosa said. “Because he has a record of credibility, it seemed clear there was nothing to proceed with in regard to him.”

DeRosa also said that limiting the investigation to conversations with Byrns was enough to comply with the diocesan policy for handling allegations of sexual abuse by priests.

The Rev. Timothy J. Lambert (above), a 44-year-old Catholic priest on a leave of absence, made sexual misconduct allegations against Brooklyn priest Joseph P. Byrns in 1998. His older brother, Robert, has made similar accusations.

But that policy, which DeRosa provided to the Globe, says allegations of clergy sexual abuse of minors will be “carefully investigated by the diocesan bishop or his delegate.” The policy also says priests found to have engaged in “inappropriate behavior” that threatens the health or well-being of minors will have their assignments terminated and be sent for “immediate psychiatric evaluation.”

Yet the policy is more lenient than those at some other dioceses because it says sexually abusive priests may be returned to active ministry and have contact with children “with professional psychiatric approval.” It also states that restrictive measures will be taken only if “deemed appropriate by the diocesan bishop.”

Lambert, for his part, said that to his knowledge no investigator working for the diocese has interviewed any of the counselors he has consulted about his abuse, or any member of his family. He said Rubino provided the diocese with copies of his psychiatric evaluations and a sworn statement by his mother, Alice, saying she learned of Lambert’s abuse when Lambert was a teenager and reported it to another priest.

“As far as I’m concerned, they didn’t investigate anything,” Lambert said.

While growing up in St. Anastasia Parish in the Douglaston section of Queens, Timothy and Robert Lambert seemed destined to take different paths.

By the sixth grade, Timothy was a conscientious altar boy grateful for the attention from Rev. Byrns, who treated him to seats at sporting events and convinced him that he was every bit as worthy as his classmates, despite his alcoholic father.

“At school, Fr. Lambert was known as `Little Father Byrns,’ which thrilled Fr. Lambert,’ ” Rubino wrote in his letter to Daily.

Robert, older than Timothy by two years, was more rebellious and liable to worry his mother by staying out late. But like his young er brother, he relied on Byrns to smooth out the rough spots in his life.

“He was like a friend,” Robert said by phone from his home in a Las Vegas suburb, speaking of Byrns. “I would stay out a lot at night and Fr. Byrns would appear out of nowhere and find me on the street and bring me back to the rectory and get me something to eat.”

It was on a night like that, Robert said, when he was about 13 years old, that Byrns sexually molested him for the first time.

“I went up in his room like I had before,” Robert said. “It was real late at night and he said, `Just sleep here. I’ll call Alice and tell her you’re here.’ “

Timothy Lambert said that when he was about 11 he, too, was molested by Byrns in his room at the church rectory. And the abuse escalated, he said, on a weekend trip to Niagara Falls with Byrns when they slept in the same room.

Neither Timothy nor Robert would discover that Byrns was allegedly molesting the other until decades later. But today they agree Timothy was victimized more often. Robert, for instance, said he does not remember being molested by Byrns on more than a couple of occasions during his teens. In 1974, Robert dropped out of high school to enlist in the Army.

Timothy, by contrast, said he was repeatedly molested over a three-year period that ended in 1974. In the letter to Daily, he provided specific details about the abuse, which he said left him physically injured on some occasions, and offered intimate details about Byrns, including the location of scars and his private telephone number.

The molestations came to a traumatic end, Timothy said, when he was a sophomore in high school and told Byrns he would no longer tolerate the abuse.

“I just told him, `This is wrong,’ “ Timothy said. In response, he said, Byrns ordered him out of the rectory and Timothy walked home alone.

When the molestation ended, Lambert said, he never repressed the memories. Nor did he keep the experience to himself. First, he said another priest and family friend, David L. Cassato, now a monsignor in the Brooklyn Diocese, sensed something wrong and coaxed Lambert into talking about the abuse.

Then Lambert’s mother said she learned of the abuse when she discovered a short note written by her son in one of his shirt pockets. A devout Catholic to this day, Alice Lambert said she confronted Byrns, who took the note from her, and then spoke with Cassato, who she said discouraged her from taking her concerns to the church pastor.

“He just said, `They’re never going to believe you,’ ” she said.

Timothy Lambert, who said he didn’t learn his mother had spoken with Cassato until 1997, remained friends with Cassato through his own ordination in 1992 and into his life as a priest in the Metuchen (N.J.) Diocese.

After he decided to do something about the abuse he says he suffered and contacted a lawyer, Lambert said Cassato agreed to back him up by providing a sworn statement. But Cassato never followed through, Lambert said.

In a brief interview in the rectory at St. Athanasius Church in Brooklyn, Cassato refused to discuss Lambert’s story. “I’m really not in a position to talk about it,” he said, before retreating behind a closed door.

Lambert said he is not able to explain why he became a priest after years of being sexually abused by a clergyman. But he did describe a continuing ambivalence that both he and his brother, Robert, felt toward Byrns – perhaps the most significant male figure in their lives.

When Lambert celebrated his first Mass, in 1992, he invited Byrns to be on hand for the occasion. And when his brother was planning to get married, he asked Byrns to officiate.

Even then, Robert said, Byrns’s first response was to ask about his fiancee’s sexual preferences and to insinuate himself into their post-wedding plans. “He came out and did the ceremony and hooked up with another priest friend in South Dakota, and we all went to watch the Yankees and the Twins play [in Minnesota], and that was our honeymoon,” Robert said. “I’m embarrassed by that now.”

Specialists in child sexual abuse said it is not uncommon for victims to feel ambivalent or even positive about their molesters.

“In a lot of cases, you see kids who are abused coming from situations of extreme emotional deprivation, where the relationship in which they’re abused is often their closest one, or the one where they have felt the most affection or approval,” said David Finkelhor, a sociologist at the University of New Hampshire who was recently named to a Boston panel designed to help Cardinal Law prevent child sexual abuse.

Timothy Lambert, for his part, said he was in touch with Byrns as late as 1997, when he called Byrns to upbraid him for failing to attend his father’s funeral and promised to do something about the sexual abuse he says he has suffered. “I said, `I’m getting a lawyer, I’m getting therapy and this is not over,’ “ Lambert recalled.

After the conversation, Lambert received therapy at Guest House, a Catholic-affiliated residential treatment center in Minnesota for alcoholics, where he told a counselor that he’d been abused by Byrns. As required under Minnesota law, the counselor reported the abuse to local authorities, and to the Brooklyn Diocese.

Lambert then told his brother about the abuse and, for the first time, learned that Robert had also been allegedly molested by Byrns.

When he returned east in 1998, Lambert met with the vicar general of the Brooklyn Diocese, Monsignor Otto Garcia, and the director of clergy personnel, Monsignor John Brown, and described the abuse he said he suffered at the hands of Byrns.

Diocesan officials promised to look into his allegations and offered to pay for therapy and medication for Lambert and his brother, Lambert said. But when Lambert later asked that he and his therapist be allowed to meet with Byrns, church officials refused.

“Up to that point, I was willing to keep it all in the club,” Lambert said. “I wasn’t looking for money or anything. I was just looking for closure and when they said `no’ – that’s when I got a lawyer.”

Oddly, church officials granted a similar request by Lambert’s brother and his therapist, but Robert said he withdrew his request to meet with Byrns in order to express support for his brother. “I wanted to back Timmy even though this happened to both of us,” he said.

When officials in the Brooklyn Diocese learned he had retained counsel, Lambert said, they expressed their displeasure by cutting off funds for his therapy and medication – even though they continued to cover similar expenses submitted by his brother.

As DeRosa said, “When he went to an attorney, it became an adversarial thing and at that point we found it inappropriate to continue and suspended that.”

According to documents provided to the Globe by Lambert, Rubino and lawyers for the Brooklyn Diocese began discussing a private settlement of Lambert’s accusations against Byrns in 1999, after Rubino sent the eight-page letter to Daily detailing the allegations.

At about the same time, church lawyers were also defending the diocese in a state Supreme Court appeal filed by Susan Langford, a woman with multiple sclerosis who alleged that a priest had sexually molested her while providing spiritual counseling.

Lambert said talks over his allegations proceeded slowly until April 2000, when Rubino told him the diocese was suddenly no longer willing to negotiate what Rubino felt was an appropriate settlement. The turnabout, Lambert said, came after lawyers for the diocese prevailed in the Langford case, a ruling that strengthened the hand of New York church officials in confronting allegations of sexual abuse by clergy.

In its 3-to-1 decision, an appellate division of the New York court did not rule on whether the Brooklyn priest had molested Langford. Instead, it said that investigating whether the priest had violated his responsibility would require an impermissible inquiry into church doctrine, which is protected by the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of religion.

The court also said that any charge that Langford had been injured by the priest was subject to the state’s one-year statute of limitations.

DeRosa said the court’s Langford decision had no bearing on negotiations over Lambert’s allegations against Byrns. But Rubino disagreed: “In hindsight, looking at the release date of the opinion, it’s clear to me that the negotiations were designed not to conclude until that opinion was published.”

Today, Lambert says he will continue to press his charges against Byrns. But he is pleading his case to a bishop who is no longer listening.

“What Bishop Daily has said is, he believes in the innocence of Fr. Byrns,” said DeRosa, adding that without new evidence, “the case is, in effect, closed.”